Managing Exposure to State Estate and Inheritance Taxes

Presented by Marianna Goldenberg

In 2017, with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the federal estate tax exemption amount was effectively doubled. Today, individual estates valued at less than $11.4 million are not subject to federal estate taxes.

This has left many Americans thinking they don’t need to worry about estate taxes at all. But there are still state estate taxes and/or inheritance taxes to keep in mind—even for estates that don’t come close to the federal exemption limit. Here, we’ll review some of the historical context, along with some techniques that can help you determine your exposure to state estate and inheritance taxes, so you can plan accordingly.

State Estate Taxes: Past and Present

Before January 1, 2005, states could impose what was known as a “sponge” or “pick-up” tax. Essentially, states were able to collect taxes on a decedent’s estate without affecting its total estate tax liability. The total estate tax liability was shared between the federal government and the states, so the states could “sponge” off the estate’s federal tax liability. After January 1, 2005, however, that system was phased out, and states had to decide whether to impose their own standalone estate tax or to carry on without estate tax revenue.

Many states are in the process of raising their estate tax exemption threshold or doing away with the estate tax altogether. Some states remain outliers, however, subjecting their residents to a low estate tax threshold. Massachusetts, for example, taxes any estate valued at more than $1 million, which has been the threshold since 2006 with no adjustment for inflation.

Until the dramatic increase in the exemption brought on by the TCJA, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, and Hawaii were prepared to set their state estate tax thresholds in lockstep with the federal exemption. They decided to settle on an exemption at or somewhere near the 2017 federal estate tax threshold, however, after the passage of the new tax law.

Estate taxes versus inheritance taxes. It is important to realize that while the terms “estate taxes” and “inheritance taxes” are sometimes used interchangeably, they typically have different definitions from a state taxation perspective:

An estate tax is a tax payable by the decedent’s representative based on the value of the decedent’s assets remaining at his or her death.

An inheritance tax is a tax imposed on the beneficiary or inheritor of a decedent’s property based on the value of what he or she receives.

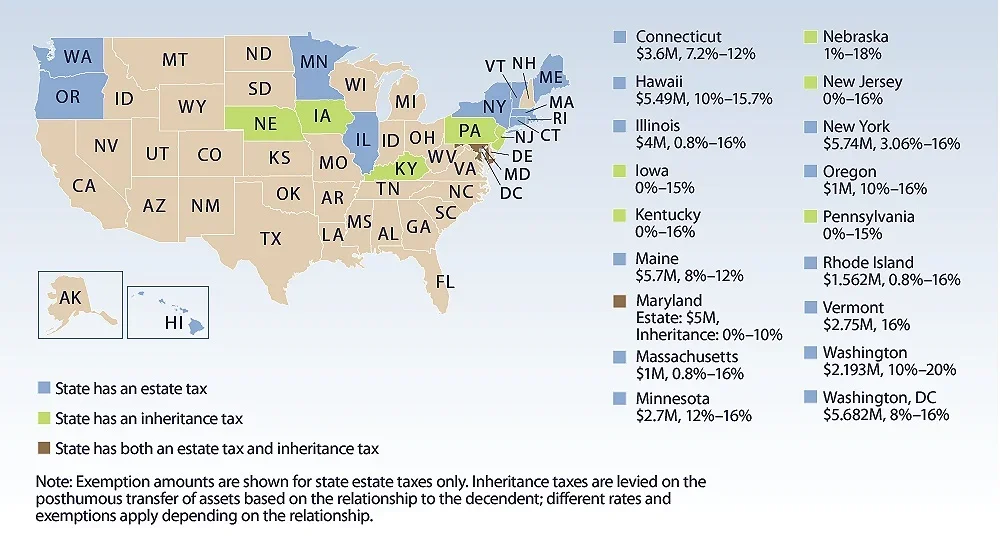

Today, 12 states and the District of Columbia impose a state estate tax, while only 6 states have an inheritance tax on the books. Maryland is the only state that has both an estate tax and an inheritance tax (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. State Estate and Inheritance Tax Rates and Exemptions for 2019

Source: Tax Foundation, Family Business Coalition, state statutes

State-Level Planning Strategies

As the state estate tax rate in any given state is typically substantially lower than the federal estate tax rate of 40 percent, it is imperative that your estate plan weighs the implications of typical estate tax planning techniques.

AB marital trust planning and gifting. The most common ways to limit state estate tax exposure are through the use of AB marital trust planning with a credit shelter trust or through lifetime gifting. Keep in mind, however, that each of these techniques can result in the eventual loss of a step-up in cost basis.

If assets pass to a credit shelter trust on the death of the first spouse, then those assets would remain in the estate of whichever spouse passes away first and, therefore, would not be eligible for the step-up in basis on the death of the second spouse. If assets are gifted during the couple’s lifetime, then the recipient of the gift would receive a carryover basis on the asset rather than a step-up in basis.

If you don’t have a comprehensive understanding of the basis of the assets being used to fund an estate tax planning technique and the potential capital gains tax that would otherwise be avoided, you could inadvertently create more of a total tax liability than intended.

Moving to a “tax-free” state. Although there is a variation in estate taxes by state, most states do not impose their own gift tax. Since the federal estate tax exemption threshold applies to gifts and estate taxes combined, those who live in a state that imposes an estate tax but not a gift tax can consider gifting assets during their lifetime to reduce their estate to a value less than their state’s estate tax threshold. Some individuals and couples choose to avoid estate tax exposure altogether by moving to states that do not impose an estate tax.

Building in flexibility. The best approach may be to build flexibility into the estate planning documents. Typically, it’s a good idea to grant the fiduciary the relevant authority or discretion to select the appropriate assets to shield the estate from state estate tax exposure, as well as maximize a stepped-up cost basis for low-basis assets.

One popular way to accomplish this goal in the context of marital planning would be to have a plan that allows the surviving spouse to disclaim specifically selected assets that he or she would otherwise inherit into a credit shelter trust. In that type of planning, the surviving spouse can be in control of weighing all the potential future tax liabilities in determining whether to shield assets from state estate taxes.

Estate Tax Planning in a Changing Environment

While the drastic change in the federal tax system has made individuals reassess their estate planning objectives, lingering state estate taxes mean that individuals cannot completely disregard estate tax planning. As the tax laws continue to change over time at the federal and state levels, it’s essential to review your estate plans periodically to ensure that you’re taking the appropriate action to mitigate the taxes that could ultimately affect your beneficiaries.

If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me at 215-486-8350 or at marianna@curowm.com.

Commonwealth Financial Network® or CURO Wealth Management does not provide legal or tax advice. You should consult a legal or tax professional regarding your individual situation. This material has been provided for general informational purposes. Although we go to great lengths to make sure our information is accurate and useful, we recommend you consult your tax, legal, or financial advisor regarding your specific circumstances

###

For Registered Representatives: Marianna Goldenberg is a financial consultant located at CURO Wealth Management, 1705 Langhorne Newtown Road, Suite One, Langhorne, PA 19047. She offers securities as a Registered Representative of Commonwealth Financial Network®, Member FINRA/SIPC. She can be reached at 215-486-8350) or at marianna@curowm.com.

Authored by the Retirement Consulting Services team at Commonwealth Financial Network.

© 2019 Commonwealth Financial Network®